One of the strangest books to come out of the 1970s fantasy art imprint Paper Tiger had to be Bruce Pennington’s Eschatus (1976). Pennington was one of the iconic science fiction and fantasy book artists of the era, working largely with New English Library. His work stood in stark contrast to the mechanical, gargantuan precisionism of Chris Foss and his imitators. Instead Pennington’s paintings portrayed an eternal twilight world of semi-organic landscapes inhabited by mutants in insect armour, or tattered, insubstantial humans that appeared to have grown out of the landscapes they inhabited. His palette alternated between bold primary colours, and faded pastels, and had echoes of Bosch grotesques and John Martin’s catastrophic biblical scenes, which made him the perfect artist to illustrate the decaying lush worlds of writers like Gene Wolfe and Clark Ashton Smith.

Eschatus was a collection of forty paintings inspired by the prophesies of Nostradamus, which Pennington re-interpreted as covering a future age from the beginning of the twenty-second century to the close of the twenty-fourth. His visual interpretations oscillate between the directly symbolic to a range of mood pieces depicting his signature decaying landscapes under dramatic skies. Given that most people would struggle to build any coherence out of the nonsensical ramblings of the original poet, Pennington does manage to construct a grand narrative of a sequence of empires of varying degrees of fascistic awfulness rising and falling before the arrival of the Great Law-Giver who presumably heralds an new age of peace.

As his own website states, Pennington worked at speed on the paintings during a six-month period, time taken up not only with the actual pieces themselves but also with tracking down the original poems and creating new translations. The result is a mixed bag. Some of the works were clearly rushed, and unfortunately tended to emphasise the difficulty he sometimes had with realistic portrayals of the human figure. The art falls into roughly three categories:

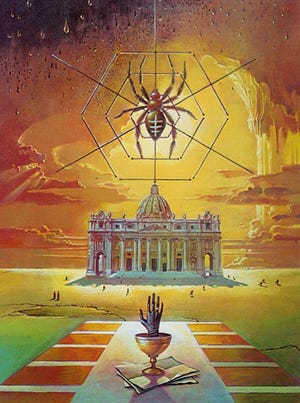

Directly symbolic pictures such as the one illustrating the quatrain ‘O vast Rome they ruin approaches’ (10-65) which shows a big spider hanging over the Vatican with a hand poking out of a chalice.

Apocalyptic battle scenes as vast armies slug it out, often with the help of flying saucers and the odd collapsing Martin-esque mountain.

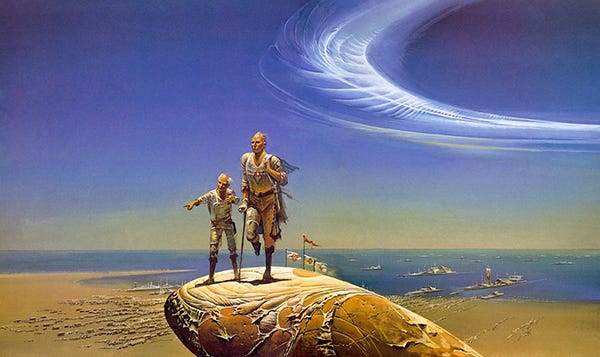

Mood pieces – either of landscapes dwarfing tiny figures or enigmatically decadent aliens pondering their empires.

Of the three the last are perhaps the most evocative. The symbolic pictures just substitute visual obscurity for linguistic, the lurid explosions and fighting armies start to look a bit similar, and the results are perhaps the most technically weak. The painting illustrating ‘The young lion will overcome the old one’ (1-35) is genuinely awful.

But among these there are some real, stunning pieces of art, that clearly show that, with a bit of discipline, Pennington really was a breath-taking science fiction and fantasy artist. My favourites are ‘The year that Saturn and Mars equal aflame’ (4-67) which is a very simple picture of a ruined city under a twilight sky but so evocative, the diptych ‘Selin Monarch Italy Peaceful’ (4-77) with its stunningly vast banners above a ice waste, ‘Peace, union will be and change’ (9-66) which shows that Pennington was perfectly capable of creating figures full of dramatic power, and the utterly sinister alien cardinal of ‘He who was well advanced in the kingdom’ (6-57).

In many ways Eschatus would have worked best as a future history of mankind such as Vance’s Dying Earth or Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun. When the art focuses on capturing a landscape or mood the results are as powerful and exciting as any of Pennington’s best work. When he tries to tie the imagery closer to the verse the results feel more constrained, with a tendency to drift into an attempt at rather heavy-handed symbolism to match the original late-Renaissance twaddle.

Oddly the book finished with 24 pages of phrases that Pennington plucked out of the prophecies. I’m not sure why they’re in the book – perhaps Paper Tiger felt the need to bulk it out to justify the extortionate £4.25 they were asking. They would probably be valuable if cut up and dropped on the floor to generate inspiring plotlines, but that would be a crime as Eschatus is not easy to find these days – you’re looking at £40 for a decent copy. Even so, as a fascinating collection of Pennington at his best and worst, and a glimpse into the kind of stuff being produced in the heady prog-rock mid-70s this is a wonderful book.