The robot teacher just exploded...

Visions of the future classroom from the 19th century to the present

The movie Class of 1999 (1990) was an almost-straight-to-video epic designed to cash in on the popularity of the Terminator movies. It’s set in a world where there’s a teacher shortage and school discipline has collapsed, so the government quite naturally decide to use decommissioned military robots as teacher substitutes. What could possibly go wrong? (The poster slogan ‘The Ultimate Teaching Machine… Out of Control’ kind of gives it away.) In real life 1999 came and went without deranged cyborgs running amok in our classrooms, but the notion of robot teachers still exercises the imagination of futurologists, as we shall see.

I work in the world of Education Technology which often dovetails quite nicely with my passion for science fiction, transhumanism and visions of future and alternate societies. A lot of the discussions at conferences and with strategic decision makers revolves around anticipating how ICT can support and enhance teaching and learning. Often it’s a case of working out which trends are valuable, and which lead to dead ends. Technology changes on a monthly basis, with cool new toys like tablets and VR appearing in a steady stream of innovation. Education moves extremely slowly, and if you add a new piece of kit to the classroom you may not see its effect for years, if not decades.

Since the dawn of the age of technological transformation writers and artists have been trying to describe schools of the future, often with hilarious results. I thought I’d walk through a number of examples, not only because they are often unintentionally funny, but also because they reveal what I think is a misconception about what education is actually for. The fact that the following examples largely proceed from the minds of people who have never taught a class is also telling. Because most of them don't really understand that education is primarily to do with human beings telling each other stuff and working out how to solve problems, they focus on the machines. In the World of Tomorrow education will be more efficient because either machines will do it, or machines will help us do it. Here's a little wander through some of the various visions these largely misguided prophets have put together.

This drawing is from Albert Robida's 1890 novel La Vingtième siècle. La vie électrique, which purported to show life in Paris in 1955. A young woman uses the téléphonoscope to study maths. Of all the examples in this article this is perhaps the most prescient, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic where so many children ended up struggling with online learning. Given that this image is 130 years old it is remarkably forward looking. The two striking things to note are a) it's a woman learning maths - in Robida's future women are equal, if not generally more accomplished than the men and b) the method of delivery is very old fashioned. A teacher who looks like an eighteenth century vicar pontificates in front of a blackboard. For those of you who remember late night, flickering black and white images of sideburns, Grateful Dead beards and kipper ties it's the Open University circa 1968 all over again.

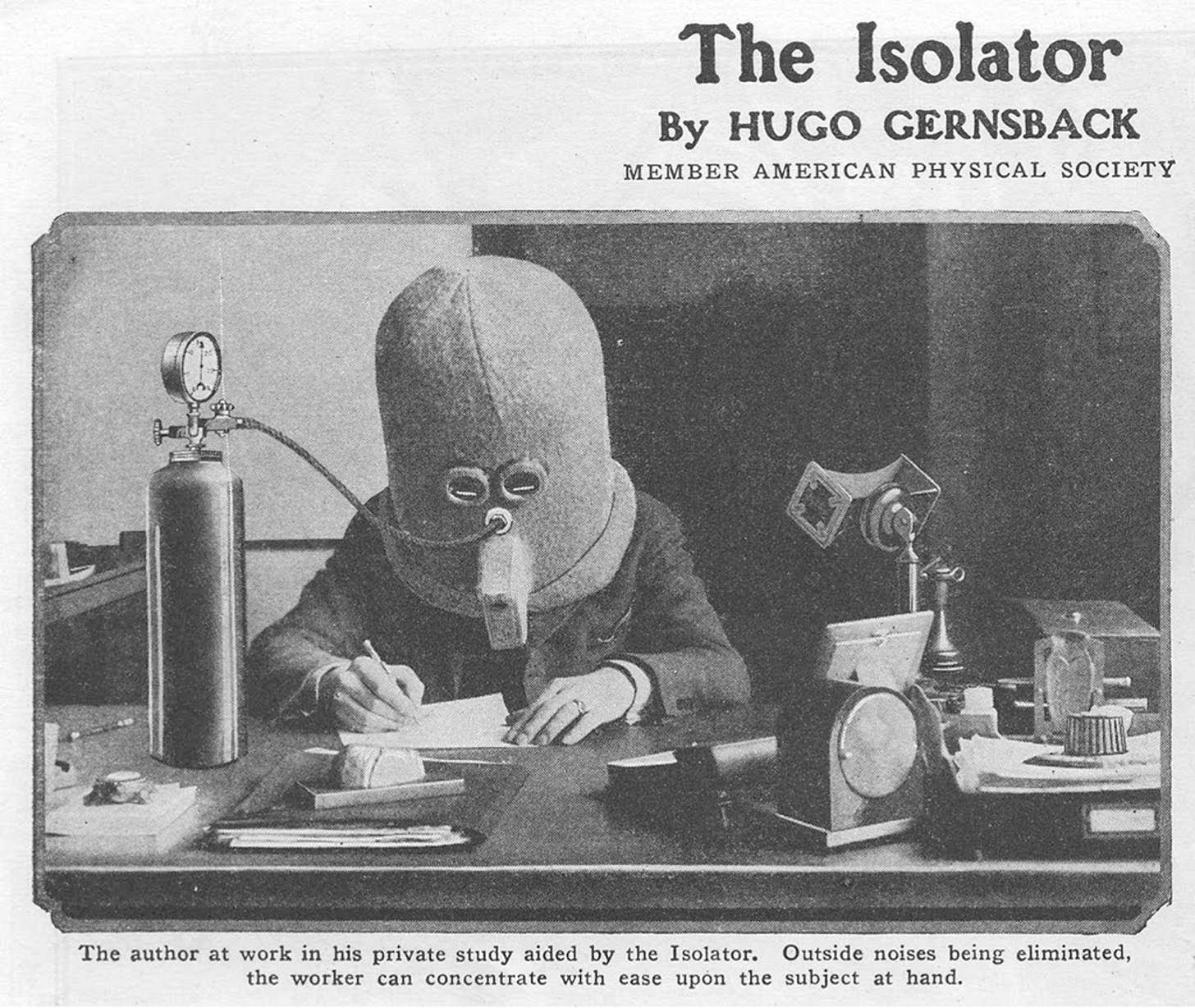

As a slight digression, this wonderful invention of Hugo Gernsback from the July 1925 issue of Science and Invention is called The Isolator and is designed to allow the dedicated student to concentrate without distractions. Putting aside the fact that it would give any Health and Safety officer the screaming hab-dabs (let's swap the oxygen cylinder for helium), it has perfect application in the modern classroom. The year after this vision hit the newsstands, Gernsback launched the first ever science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories.

What is remarkable about technological visions of the classroom is that they often have an extremely regressive understanding of the process of education. Even with the most advanced machinery and computers, the act of studying is still seen as the transmission of a traditional fact-based curriculum by a teacher lecturing from the front to an audience of silent kids sat in rows. This vision of the school of tomorrow from the 1950s is a perfect example. What is telling is that many of the ICT systems I come across in education differ very little from this paradigm. Teacher talks - whether via a TV screen or in the figure of a computer or avatar - and students listen.

The cartoon below from a Japanese magazine in the 1960s shows exactly the same paradigm. Computers will teach in the class using video while little robot helpers belt the kids over the head with red bludgeons if they get their sums wrong.

Falling firmly into the ‘just because we can do it doesn’t mean we should’ category is this English Language Robot Teacher. For me this image sums up everything wrong with technology in the classroom, and what happens when the perceived coolness of the machinery completely overrides the education side of things. To my mind teaching languages is about communication between humans - people talking to people. Racial stereotypes aside (English is spoken by pretty, blue eyed, white, American blondes) this seems counter to the entire principle of foreign language instruction.

Learning without any effort whatsoever is the cyberpunk paradigm displayed to great effect in The Matrix (1999). Skills and knowledge are acquired by simply slotting in a chip to the back of your neck, or wiring yourself up to a computer. After twitching around for a few seconds you’re an expert on Kung Fu, Quantum Mechanics and 19th century Russian literature. In one sense it’s a very attractive notion, and the basis for 'learn while you are asleep by listening to a tape recorder' industry of the '60s and '70s, but once again it betrays a very mechanistic view of learning as just stuffing a machine (the brain) with data.

Finally it's back to the 1930s and Alexander Korda’s film of H. G. Wells’ Things to Come to offer a paradigm of future education which is not completely technology-centric. In a charming scene towards the end of the film an old man explains history to his granddaughter with the aid of a giant television. Putting aside the hideously grating voice of the infant, the education paradigm it's offering is that of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's 1762 classic, Emile. In his book Rousseau suggested learning was best done by the child exploring the world and asking intelligent questions of a patient mentor. As the old ways of learning break down we may well find ourselves moving back towards this approach which, thankfully, relies primarily on human interaction and not machines.

As someone who enjoyed the social side of school but found the learning side difficult, I agree that the human interaction is important. But living in France and struggling to become fluent in French, I wish I could plug myself in to a computer and become fluent in 30 seconds.