Not surprisingly over the past few years people's ideas of British post-war fantasy have been been dominated by J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, but his nostalgic Pre-Raphaelite vision of an idealised medieval world is not the only non-realistic writing to come tumbling out of the horror of World War II. Alongside the tales of Tolkien and C. S. Lewis there's another darker and more grotesque strand of fantasy. Mervyn Peake's Titus Groan (1946) belongs to this second, absurdist tradition. His Gormenghast trilogy, of which Titus Groan is the first book, is, to my mind, best described as Charles Dickens and Franz Kafka on Acid.

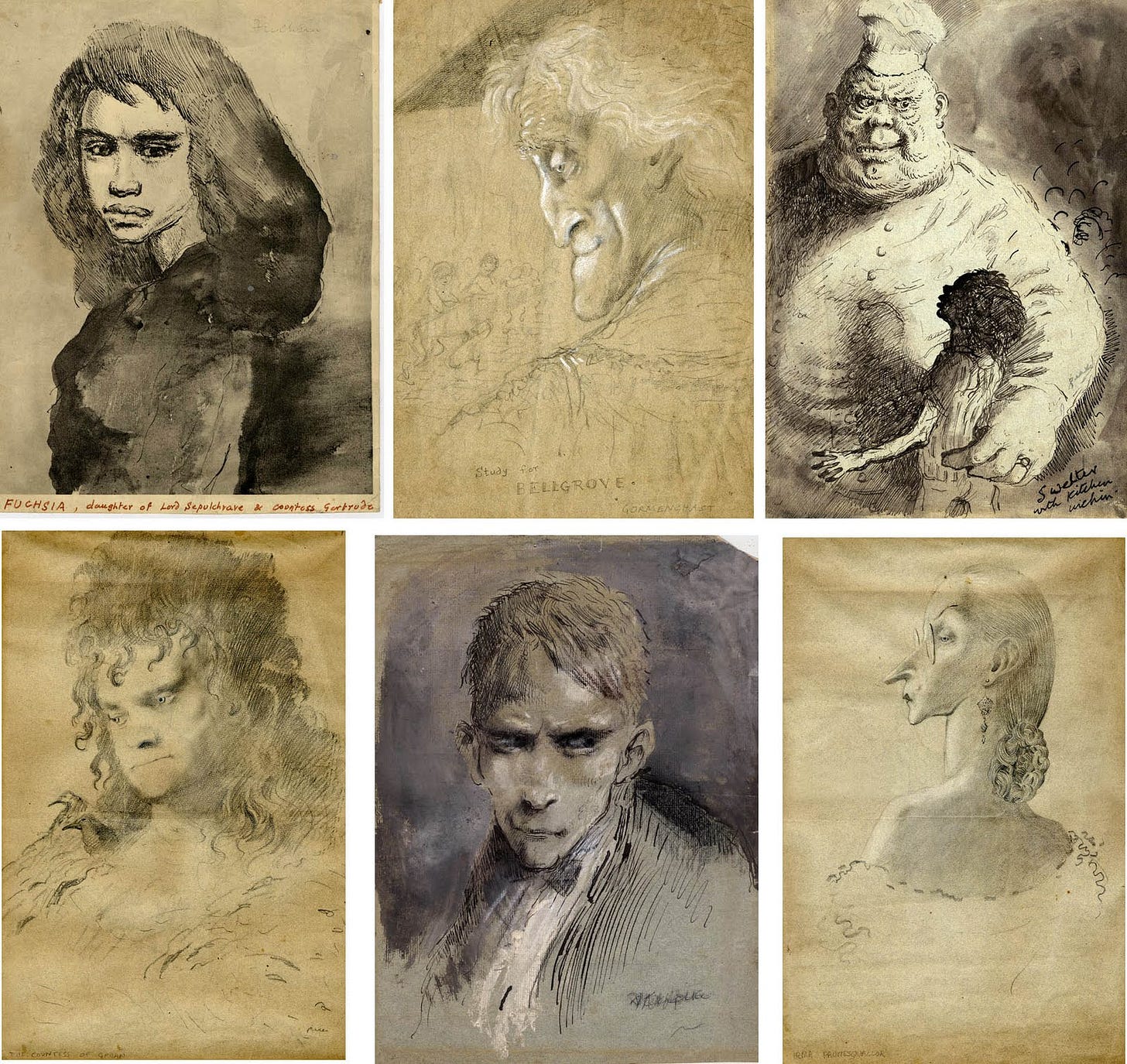

Mervyn Peake served in the Royal Engineers during World War II. He began writing Titus Groan partly as therapy following a nervous breakdown, and it shows. He was first and foremost an artist and this training also comes across in the unbelievably dense prose of the book, as well as the haunting portraits he produced of the characters from the novel. Titus Groan tells of a dynastic family of bizarre eccentrics living in the vast castle of Gormenghast. This world is a surreal combination of ancient masonry and mid-20th century bourgeois domesticity, where peeling wallpaper mingles with crumbling gargoyles and images plucked straight from dreams (a mare and her foal swim in a lake on top of a vast tower, two sisters have tea on the trunk of a tree that grows horizontally from a vast wall).

The inhabitants of Gormenghast, Lord Sepulchrave Earl of Groan, his family and servants, live out their lives bound to innumerable arcane daily rituals and laws. People take on the characteristics of objects (the slab-faced grey scrubbers who wash the floors of the huge castle kitchens) and objects become imbued with a bizarre life, not least the castle itself which seems to be infinite. There's not a lot of plot in Titus Groan, the eponymous hero is still only one year old at the end of the book, though we see the beginning of the rise of the kitchen boy Steerpike whose assumption of power will dominate the second book in the series, Gormenghast.

Mark Spilka wrote a comparative study of Charles Dickens and Franz Kafka in 1969 in which he argued that both writers suffered from an ‘arrested childhood consciousness’ due to their troubled relationship with their respective fathers (wastrel in Dickens’ case, bully in Kafka’s). Despite their stylistic differences Spilka spotted common themes peculiar to a type of writing known as Grotesque Fantasy. Elements include:

An absurd world with ridiculous rules and rituals made for others (‘adults’) not the protagonist (surrogate child)

People taking on the properties of objects, objects becoming like people. Characters are defined by exaggerated features and verbal tics

Urban landscapes and architecture that appear infinite and oppressive

Oscillating feelings of disgust, horror and humour so neither the reader nor the protagonist knows how to react

Bits of the body escape and take on lives of their own

Much of this is embedded in Titus Groan. Although Peake didn’t share a similar toxic childhood as Peake and Kafka, his books seem to be carrying on the same absurdist and grotesque dream-like traditions that can be found in the earlier writers’ books. A lot of this perhaps stems from his early life living in a missionary family in China, very much an outsider in a world not made for people like him and with a colossal history of ancient and (to outsiders) incomprehensible traditions.

Peake's style is obsessively lush. He's happy to spend paragraphs describing damp stains on a ceiling or the drip of wax from a candelabra. At one point, during a banquet, he suddenly flips into a stream of consciousness study of each of the main participants. For readers used to the plot-driven excitement of books like the Game of Thrones series, Peake can seem a heavy and occasionally pointless slog. But I think that Titus Groan, despite its length, is a book to be read very slowly and savoured for its remarkably visual evocation of a completely bizarre world. To my mind it's a far more interesting and disturbing book than The Lord of the Rings, and a classic example of Grotesque Fantasy.

I have coined the word 'Gormenghastly' to describe a particular sort of stately home: one with a lot of eccentric contents and in a state of some dilapidation. It came to me when visiting Calke Abbey in Derbyshire and the word seemed highly apposite.